When Oppo Doesn't Matter

I helped cost Bill Cassidy ~$200,000. He beat us with five words from a website.

One of the odder things I can say about my career is that I cost Bill Cassidy roughly $200,000, adjusting for inflation1. It was the culmination of a year’s work of being very very annoying and finally landing my white whale hit of the cycle. Every researcher has a similar story—the oppo you’ve been chasing since you first caught a glimpse of it surfacing in the ocean of documents you obsess over. Your pitch is your harpoon. Sharpen, reload, and re-fire until you get it to stick in the monster’s flanks.

In 2014, I was Research Director for Senator Mary Landrieu, facing off against Congressman Bill Cassidy. The whale was this: Cassidy was collecting a taxpayer salary for work he wasn’t doing.

Cassidy had been collecting $20,000 per year from Louisiana State University since being elected to Congress, slightly below the cap on outside income for members. Before DC, he’d been a practicing physician and faculty member at LSU’s Health Sciences Center. In his ads and nearly every appearance, he emphasized he’d continued his calling even after being elected to the House.

His financial disclosures claimed this salary merely covered his expenses for teaching. That didn’t sit right with me. Thanks to my brilliant counterpart at the DSCC, we sent records requests to every public entity Cassidy had touched, including LSU. When the response came back months later, we learned LSU agreed to continue paying him 20% of his base $100,000 salary (on total compensation north of $300,000) in return for Cassidy working one day per week. Nothing about expenses. Interesting!

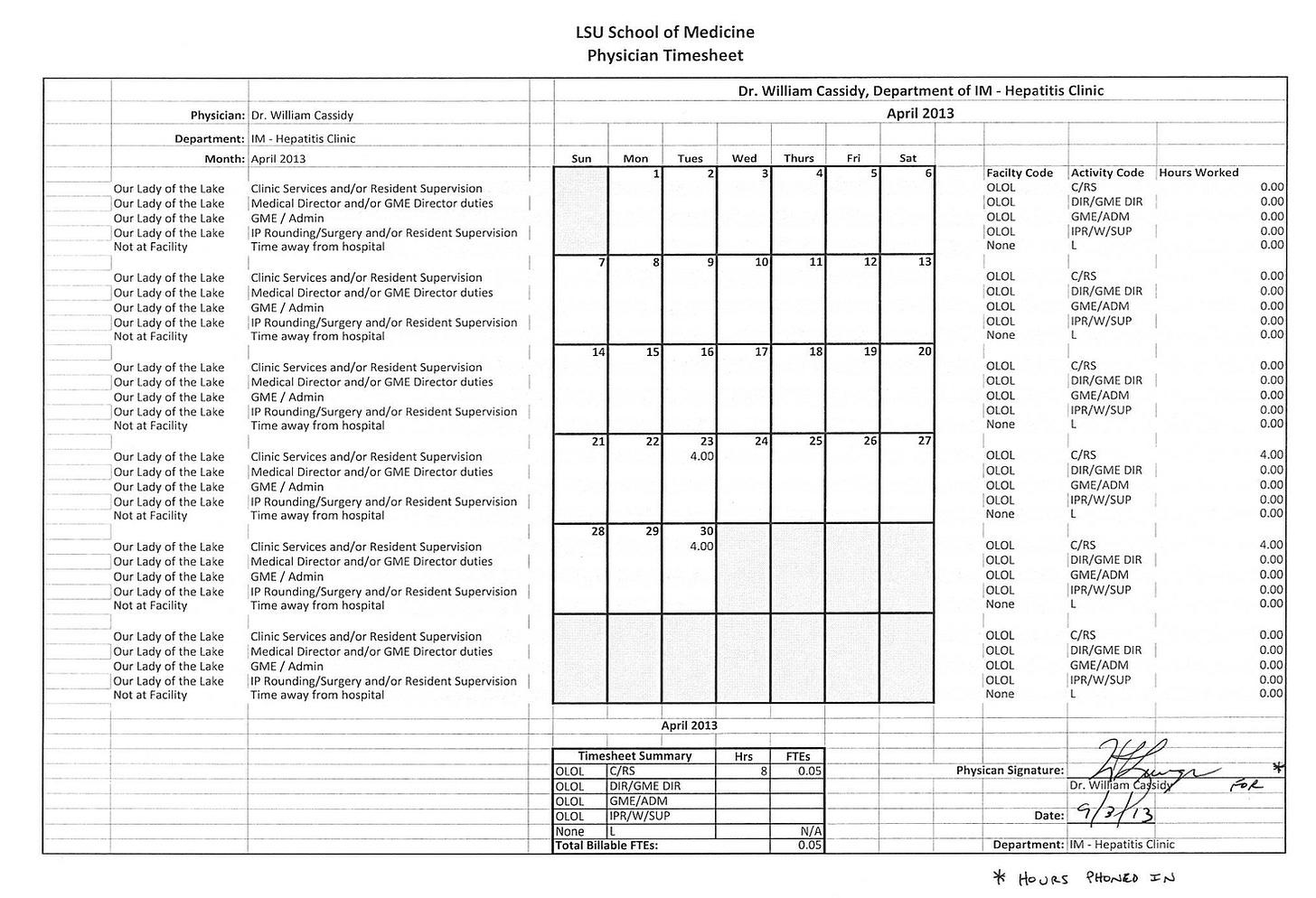

We even got emails from Cassidy himself claiming he’d keep a “paper log” and “a folder in case there are questions.” An LSU official fretted: “We are going to really have to spell out exactly what it is he does for us for his remuneration” because “this scenario will be a very auditable item.” We immediately sent another records request explicitly invoking those words, asking for time sheets, logs, anything. More waiting.

The campaign bumbled on as we began to sink in what was clearly a red wave. By summer, we had our response: LSU could only provide seven months of time sheets. On those, Cassidy reported working 7.5 to 15 hours a month. Not the 7.5 hours per week he’d agreed to! Cross-checking with the congressional record showed half the days he listed overlapped with him voting in DC or on official travel. Incomplete, but enough to show he wasn’t meeting his commitments.

The Cassidy campaign was ready. Every pitch got a deflection: This was LSU’s fault, he’s an at-will employee. Actually the salary just covered expenses. Actually just malpractice insurance. But his own correspondence with the House Ethics Committee contradicted him, LSU provided insurance on top of the salary, he had tenure, and on and on. Still didn’t stick.

We eventually got 16 total time sheets out of 63 months. The salary never changed despite wildly varying reported hours. Some he signed, some he didn’t; three sheets even literally said he “phoned in.” I kept refining the pitch but could never land the story I wanted. One particularly humid night I sat in a bar with an investigative reporter from local TV. Slicked back hair, double shots. I walked him through the hit line by line. He loved it. It never made the news.

We had already failed to win the first round and knew we were going to lose, but at that point I just wanted to bloody his nose. I’d harassed every reporter who would listen and gotten nothing but credulous evasions. It was time to get creative. We handed everything to local bloggers on the promise they’d post the records themselves. Once they were out there for everyone to see, we called a press conference with blown-up copies of his time sheets. The Senator demanded Cassidy prove he wasn’t stealing from taxpayers. If traditional outlets wouldn’t write the story, they’d definitely write about the accusation. We put it in ads, hammered it in our last debate.

The hit was finally in the air.

The Cassidy team scoffed. LSU announced an audit. We lost the runoff. (Though hey, we did two points better than in the first round!)

Months later, after I’d long since left Louisiana, LSU unveiled their findings. They admitted Cassidy failed to “adequately” document his work and roughly 75% of his time sheets were missing or never submitted. But based on testimony from a colleague claiming she saw his white boards full, they determined Cassidy “provided services equal to at least that of his compensation.” LSU found that LSU did nothing wrong. The Chancellor even said they wanted to keep him on payroll.

And yet: upon entering the Senate, Cassidy stopped collecting that salary. His last reported payment was a little under $7,000 in 2014. From 2015 through 2022, he reported no outside income at all. Added up and adjusting for inflation, that’s over $200,000 in lost income.

(That is until 2023 and 2024, when suddenly a new LSU salary appeared on his disclosure. Right in time for his upcoming re-election! Hopefully he’s kept better records this time.)

I’d like to think we made it too politically risky. That counts for something, right?

Except here’s what was actually working while I played Ahab with time sheets and FOIA requests:

“Mary Landrieu voted with Obama 97% of the time.”

That was it. That was effectively Cassidy’s entire campaign. Easy to understand, easier to remember. It came from a website that tracked which bills the White House indicated an opinion on, less than one day’s work to find. In Louisiana, Obama’s approval rating was somewhere between “disastrous” and “catastrophic.” Landrieu was a Democrat. Obama was a Democrat. Voters filled in the gap themselves.

I tried to counter with my own gimmick statistic: Cassidy voted for 97% of the bills Obama signed in the 113th Congress. Which was true! And also completely stupid and ineffective.

Our own polling told a similar story. Our strongest attacks on Cassidy? His support for the Republican Study Committee budget. His vote to raise the Social Security retirement age. His support for cutting Medicare and Medicaid. Nothing complex. No document diving required. Just: he voted to raise the retirement age and cut benefits. One sentence. Everyone understood it.

I remember being put on the phone with James Carville one afternoon. Louisiana native, Clinton war room legend. Basically a pundit by then but a desperate campaign will turn to anywhere for advice. He told me I needed “ice in your veins” and to clobber Cassidy on Social Security. Make it hurt.

“James,” I said, “we’re already running that on TV. It’s been up for weeks.”

There was a pause.

“Well,” he said, “keep it up.”

We were doing exactly what you’re supposed to do, hitting him on unpopular positions with clear stakes. We had the votes, the pain they would cause, everything documented. It just didn’t matter as much as voting 97% with Obama. Sometimes you’re swimming against a tide that is too strong.

I’d seen this before. On Obama 2012, I worked on the Bain Capital team. I had a passion hit about how Bain Capital investments restructured their pensions into “cash-balance” plans. Complex stuff, but the upshot is the transition often ending up hurting the oldest employees the most while saving the employer money. I thought it was a perfect example of how Romney’s policies would harm near or current retirees. Extremely satisfying research. Never got it written, didn’t need to bother. Voters didn’t need financial analysis, they just needed to hear “corporate raider,” “Swiss bank account,” and “shipping jobs overseas.”

Even perhaps the most famous hit of the cycle, the “47%” clip, just appeared online one day. A Mother Jones reporter was handed a video from someone who stuck a camera phone in a fundraiser. No sophisticated research required, no campaign involvement needed at all, and no explanation needed for voters already skeptical of the private equity executive turned politician.

The best hits are the ones that reach escape velocity. They’re straightforward to remember, clear enough to repeat, and they connect to something voters are already inclined to believe. All the detective work in the world doesn’t matter if no one will care.

The art of opposition research is providing vocabulary for what voters feel but cannot yet express. Voters in Louisiana didn’t like Obama. They didn’t trust Democrats. “97% with Obama” gave them language for the idea that Landrieu wasn’t really on their side. It was validation to vote against her.

I still believe my Cassidy research proved he was billing taxpayers for work he didn’t do. I had LSU officials on record worrying about audits. I had his own emails promising documentation he never provided. I eventually got an official investigation admitting 75% of his time sheets were missing. None of it mattered. I couldn’t get reporters to write it. And even if I had, would ‘inadequately documenting work hours at a public university’ connect to any feeling Louisiana voters had about Bill Cassidy?

The more complex a story, the more opportunities to explain it away. Even if you can get it written up, motivated reasoning is powerful. Persuasion is hard. If a voter doesn’t already want to believe something about a candidate, you’re asking them to follow a complicated argument. Most won’t.

There are always exceptions, but I think it’s a good rule for researchers. It’s made me come around on the humble campaign finance hit, where you check who donated to whom and what they voted for. Very little art there. And the arrow of causation is often wrong: politicians get contributions because of what they support, rather than supporting things in return for contributions. But everyone believes politicians are corrupt and bought off, so why not embrace it? It’s much easier to fit in a post, ad, or infographic. Sometimes you might even be right.

It’s also why issue positions and votes can be so powerful. Everyone understands ‘he voted for X’ or ‘she voted against Y.’ Or ‘they agreed’ or ‘disagreed with their party on Z.’ These are very simple cues for voters to recognize. There’s no complexity to deflect, you either supported it or you didn’t. The candidate has to survive the most uncharitable explanation, and that’s on them.

And when conditions are right, simple attacks can overcome even partisan lean. Republican Larry Hogan won Maryland’s governorship in 2014 by repackaging a ‘storm management fee’ into a ‘rain tax,’ distilling everything voters disliked about Democrats into two words. The next year in Louisiana, John Bel Edwards revived David Vitter’s 2007 prostitution scandal, contrasting it with his own record as a Ranger School graduate and West Point alum. Both benefited from unpopular incumbents and angry electorates. But their messages worked because they were simple.

I love playing detective. There’s nothing as satisfying as finding something someone tried to hide, building the case brick by brick, finally forcing it into the open. The mystique is real and I understand why people are drawn to it. Part of me still wonders if we’d gotten those records out earlier, maybe it would have mattered more. But I know that’s almost certainly wrong.

Ultimately the best oppo isn’t the fanciest detective work. It’s finding the words that let the voters say what they want to think. Sometimes that means sophisticated research that becomes a scandal your opponent can’t shake . Sometimes it’s just a statistic on a website.

The ragpicker sorts through garbage to find what someone else can actually use. I cost Bill Cassidy $200,000 with a year of digging and pitching. His campaign beat us by looking up a number on a website.2

That’s the job.

Assuming he would have collected an additional $20,000 a year from 2015 through 2022, calculated using CPI-U (NSA), annual averages for 2015-2022 and a Sep-2025 index of 324.800.

And by being a Republican in Louisiana in 2014.

You hit the nail on the head re: campaign finance hits. When I am starting a new project it's usually one of the first things I work on because it's relatively simple to assemble and is a super easy to understand hit for voters. Also, crucially, reporters can easily understand it and write about it in an effective manner, which is sometimes just as important (if a reporter understands it easily they will probably write the story!)

I had a really similarly esoteric hit on a campaign about four years ago. I was obsessed with getting it over the finish line and it just never quite got there. It'll sit in my back pocket as a bar story until the end of time.

What are the examples of actually complex scandals that sunk candidates? Like of course everything can be boiled down to a simple phrase. But what are the times where something actually really hurt a pol even if it needed a bit of math?